Topic of the week:

A trifecta (always wanted to use this word) of interest rates, inflation and borrowing costs. Inflation and interest rates were arguably the main topics over the last few years, or at least the primary concern amongst economists and central bankers.

If you're one of the normal people who don't eagerly mark the dates of FOMC meetings on their calendars, don't worry - we'll bring you up to speed on what you need to know.

These meetings, which are led by Jerome Powell, the head of the US Central Bank, are where key decisions about interest rates are made, akin to a thumbs up or down verdict in ancient Sparta (but for interest rates).

While we briefly mentioned inflation here and there in some of our previous issues, like inflation hedging assets and certain macroeconomic indicator overview amongst OECD countries (shameless plug here), in this newsletter issue we’ve put a lot more emphasis on it, and how central banks have been trying to tame it. It’s only right we finally did it, given the significance of this topic over the last couple of years.

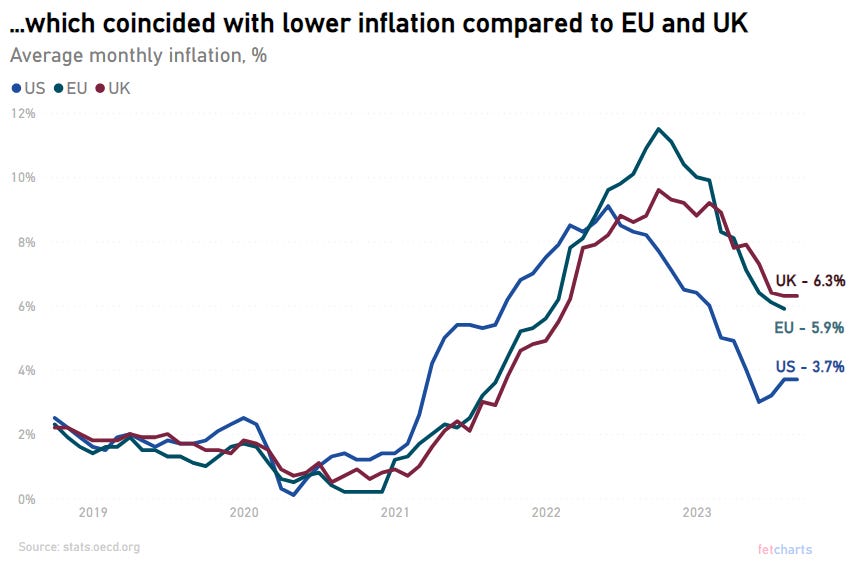

The outburst of inflation

Prior to late 2021, inflation in Europe and the US hasn't been a particular nuisance for more than several decades. However, the onset of COVID-19 pandemic resulted in numerous stimulus checks provided by some governments around the world to alleviate some of the pressure from small businesses, families and people in need. Consequently, this led to the world’s biggest economy, United States, see its central bank assets balloon from approximately $4T in February of 2020 to ~$7T in a matter of months.

Once the restrictions were lifted, all hell broke loose (metaphorically speaking of course). The extra savings, which skyrocketed to $6T in April of 2020 in the US, and all of the pent up demand was unleashed into the economy (by the way, the savings part is an excerpt from our previous newsletter - last plug, I promise), which sooner or later, you guessed it - resulted in inflation.

Central banks intervention to tame inflation

One of the first weapons to fight inflation, at least from a central banker’s perspective, was to raise interest rates. All the major central banks had cut interest rates prior to that with the onset of the pandemic, and rates were hovering around 0 - 0.25% at the very beginning of 2022. This meant, at least in theory, that there was enough of a leeway for central banks to start raising rates.

The Federal reserve raised interest rates at such a pace, which was not seen since the 1980s. Similarly, the European Central Bank (ECB) raised interest rates at the fastest pace in the euro currency history. In late 2022 Bank of England (BoE) did not want to miss out on the party and had quite a trick up its sleeve as well - the BoE raised interest rates by 75 basis points - the largest rate increase for BoE not seen since 1989.

Consequently, the current interest rates are one of the highest not seen in a long time. For example, the Federal reserve funds rate is the highest it’s been for approximately 15 years, which was not seen since prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of ‘08.

Even though the floor from which central banks started to raise interest rates was low, there were some unprecedented moves made, like the 75 bps increases (the FED had an eye-watering, or should we say wallet-flattening, four 75 bps increases back-to-back in 2022).

Rise of borrowing costs

For banks in Europe a common reference point when determining the average interest rate to charge when lending money (excluding the margin charged by the bank) is EURIBOR. For dollar-denominated loans, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) relatively recently replaced the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). Unsurprisingly, once the interest rate hikes began, lending costs started to follow suit.

If we took EU high yield or US BB rated company average bond yield as a proxy, which are considered just below investment grade and more speculative, at the very beginning of 2022 such yields were hovering around 3.5 - 4%. In recent months the yields for both the average EU high yield and a US BB graded company bond has been gradually climbing towards 8%.

If you’re a frequent reader of fetcharts, you’ve probably noticed the changes to our new (and hopefully improved) chart design. Let us know what you think in the poll below:

Average consumer outsmarts corporates?

Conversely, the average mortgage borrower in the US seems to be doing a lot better than the average company, at least when it comes to mortgage interest payments.

According to a survey by Zillow it was estimated that ~80% of US mortgage owners borrowed with an annual interest rate of less than 5%, meaning they have fixed their rates prior to the aggressive hiking of rates by central banks.

Of course, mortgage is only part of the puzzle (as interest is paid on auto loans, credit cards, etc.). However, it’s by far the largest portion for an individual consumer.

In Europe the story is more nuanced due to differences amongst each country. For example, borrowers in France had better protection against rising interest rates, as majority of the mortgages in France are with a long-term fixed interest rate - only around 5% of French mortgages are issued on a variable interest rate basis.

Conversely, people in Spain were less fortunate, as variable interest rates tend to dominate, amounting to 75% of the current mortgage portfolio.

So what?

Tough times called for drastic measures. With raging inflation reaching double digits during its peak, central banks had to react quickly, which led to fastest interest rate raises not seen in decades.

Rising rates played a part in the almost 2x increase of the average company bond yield within the Euro High Yield and US BB indices in the span of less than two years.

On the other hand, the average mortgage holder in most developed economies was left relatively unfazed. For instance, around 80% of US mortgage owners seem to have managed to fix their rates prior to the aggressive interest rate hiking.

And inflation? It’s been trending downwards, finally. So, is it safe to say that the central banks have managed to pull a “soft landing”, at least so far? Up to this point, it appears that the broader economy and the financial system has not suffered major setbacks, although this cannot be said for Silicon Valley Bank (a cheap shot, we admit).

However, there are several factors that may be of concern: companies who took up debt with variable rates in the past few years have had their interest payments increase exponentially, putting pressure on their cash flows. Additionally, a tight labour market, and whilst declining, but still above central bank target inflation, continue to put pressure on company margins - all of which is nothing to take lightly.

While central bankers have shifted towards a more neutral stance recently taking a pause in raising interest rates, they remain adamant that, if needed, future rate hikes are not completely out of the question just yet.

That’s all for this one, see you next week!

Want no BS, witty insights about the Economy, Finance and Tech Start ups with clear visuals weekly?

Sign up for free below.

this just summed up the the past few years for me. thank you.